One of the common questions we get about Land Value Rates (LVR) is about whether it’ll be progressive. Progressive policies are those where the benefits are biggest for those who are less well off. We’ll look at this question (with a specific focus on Wellington) and find that yes, LVR is progressive, in addition to its many other benefits.

LVR is progressive in the long run

In the long run, LVR will mean under-used properties are sold to people who want to use the land for productive activities. They develop their properties and the whole city benefits as we experience more growth and better land use. But beyond that, building more houses is really good for the poorest people who face extremely high housing costs as a share of their income. As supply increases, housing cost decreases, and average housing quality increases. Looking out for the most vulnerable people in our city means recognising we need to build more houses.

A policy being progressive in the long run should be enough for policymakers to view it as progressive - there’s no use saving people a few dollars today if it means costing them thousands in the years to come. But to end any possibility of capital value rates being more progressive for any brief period of time we’re going to run you through why this policy is progressive in the short run too.

Renters don’t pay LVR

The first thing to know is that renters don’t pay LVR - it is not passed on from landlord to tenant in their rent bill. This may seem counter-intuitive, but there’s a huge body of theoretical and empirical work showing this to be true. The basic idea comes from the fact that land is fixed in supply, which means that the only thing determining land rent is demand. LVR doesn’t affect demand, so it can’t affect your rent. In other words: landlords are already charging the highest land rent they can, they can’t put it any higher arbitrarily - if they could, they would’ve done it already. We will be writing more about this specific point soon.

Renters are lower-income

The first point matters a lot because renters aren’t economically the same as homeowners - renters tend to be a lot poorer.

The above graph shows estimated median household income for each suburb in Wellington, by homeowners (blue) and renters (orange). As you can see, renters are lower-income than homeowners in every single suburb. This is certainly not to say that all homeowners are rich, but there is a serious gap here. Additionally, this graph only covers income, and doesn’t look at wealth. The wealth gap between homeowners and renters is even bigger than the income gap (intuitively - the main asset most people own is their house).

The takeaway here is that the people who are the worst off tend to be renters, and renters will not pay more under LVR in the short-run.

This matters hugely when trying to understand if a policy is progressive, because if you compare the change in rates for a suburb to some metric of everyone’s income, you end up attributing the penalties on unproductive property owners to those lower-income renters who occupy their damp and mouldy homes. That’s why our analysis takes two metrics, median homeowner income and property value (a proxy for homeowner wealth), and compares them to the median rates change in a given suburb.

LVR is progressive among homeowners

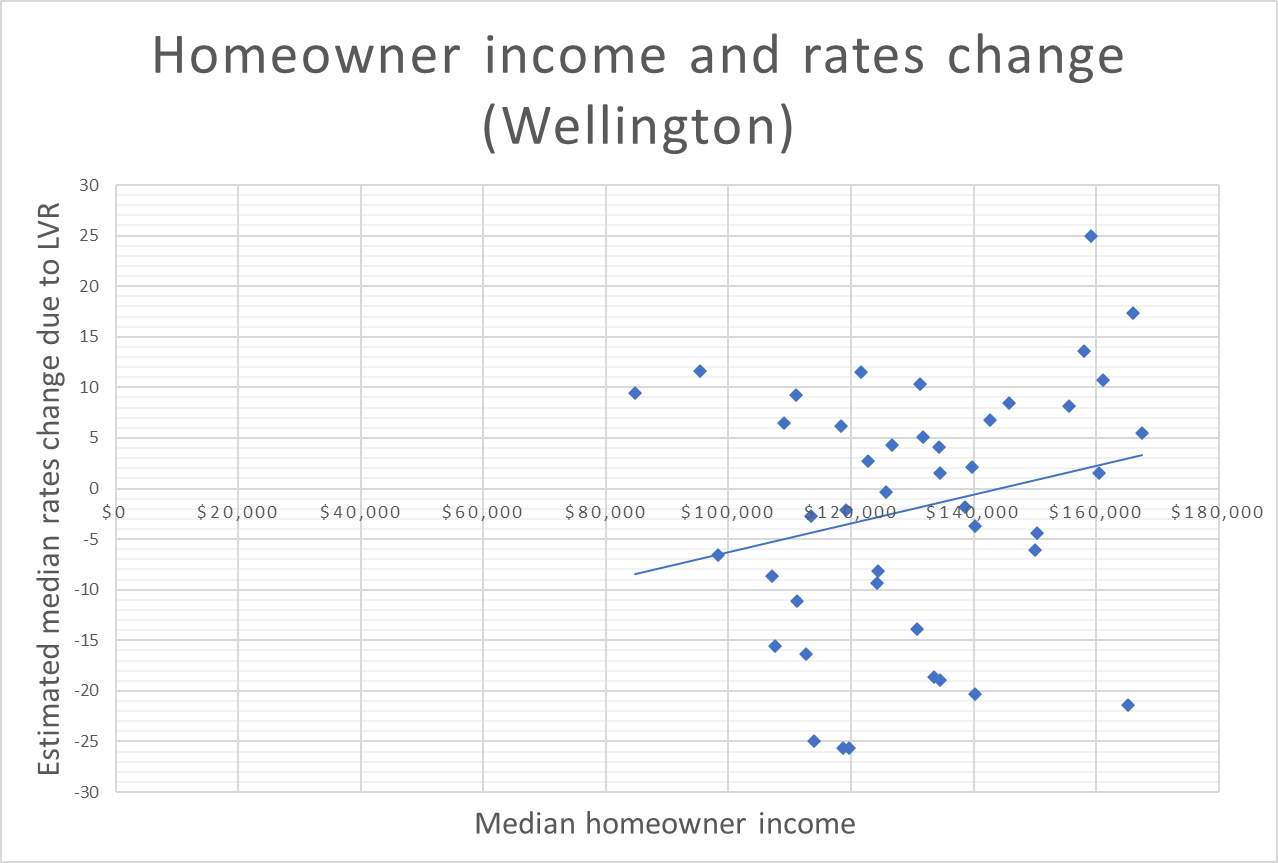

As for property owners, many will see their rates bill change. Fortunately, the policy is progressive among this group, compared to the current system:

In this graph, each data point (dot) is a suburb. As you can see, the positive slope shows that richer suburbs are likelier to get a rates increase and lower-income suburbs are likelier to get a rates cut if we switch to LVR. Overall, the median residential property gets a 4.4% rates cut from switching to LVR (without costing the council a dime) and that cut is likely to be bigger for people on lower incomes. The estimates for the changes in rates paid (residential-only) come from Common Ground Aotearoa’s own modeling, which uses official WCC data.

LVR is progressive by property value

As well as looking at incomes, we could also look at property values to determine how progressive land value rates are. After all, property values are the thing we’re interested in for rates, and we want to make sure people with lower property values are faring at least as well as people with higher property values. In fact, LVR is incredibly progressive by property value:

If a homeowner’s property is worth $1.6M or less, chances are they are looking at a rates cut, while people with property worth $600K or less are looking at a huge drop in rates. That’s progressive.

Why is this the case? Firstly, because there’s a lot more range in land values than property values. If you compare a house in a lower-income suburb to a house in a higher-income suburb, the latter could have five times the land value of the former, but not much more improvement value (total minus land value). So if you look at properties that have disproportionately high land values (i.e. those that likely pay more under LVR), they are generally high value overall. Secondly, a lot of the cheapest properties in Wellington are flats & apartments and those tend to have less land value due to density.

LVR is a progressive policy

To conclude: if Wellington City Council makes a shift to land value rates this year, a majority of homeowners will see lower rates - especially those with less expensive property - and renters will be better off as we build more housing.

Great stuff.

Your readers might be interested in similar analysis from Victoria:

https://osf.io/download/5ddb67506fc7690009d6cfe7/